How Pandemic Waivers and Smart Operations Turned a Meal Program Into a Profitable Business

Food Service Management (Catering) Companies have always been integral to Federal Child Nutrition Programs, and many of the largest food service companies, such as Sodexo, Aramark, and Taher, Inc., have specific divisions targeting child nutrition.

Taher, Inc., is even headquartered in Minnetonka, MN. Making money from Federal Child Nutrition Programs isn’t limited to large corporations. Eagan-based CKC Good Food is a Minnesota-owned small food service business serving schools, private facilities, child care centers, and non-school programs. There are many others, even smaller, which service a center or two or a school or two.

All these businesses do this for profit, not charity, and nothing is wrong with that.

Even schools have been making a surplus (not a profit due to their non-profit status) on the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) and Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) before and during the pandemic.

A review of financial records from the Minnesota Department of Education indicated that in 2020, St. Paul ISD #625 had a surplus of over $3.5 million from SFSP and CACFP, while Minneapolis Special District #1's surplus in these two nutrition programs was over $1.5 million. This trend doesn’t hold across the board, but many of the programs reporting data in 2020 showed surpluses in SFSP in particular.

Everything changed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to an article in the August 2021 edition of the Association of Metropolitan Schools Connections News,

SPPS has used funding from the United States Department of Agriculture’s Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) to provide meals during the pandemic. Typically, SPPS serves 3,000-6,000 meals each day during the summer. Last year that number rose to as many as 173,000 meals in a day. “This trend demonstrates how much can be accomplished when the SFSP rules are modified in a manner that is flexible and works better for families, “ says Koppen. “Participation in the meal program we are seeing today is likely the result of these improved program rules, along with increased need in our communities.”

Saint Paul Public Schools (SPPS) saw a 2783% increase in meal demand during the pandemic. That is a staggering increase and well beyond the 33,062 enrollment in SPPS.

Ms. Koppen knows what she is doing when she speaks about how the rule changes allowed better service to families; she was named the Midwest Regional Director of the Year in 2021. Her LinkedIn shows how she increased SPPS’s net food service income by $3.1 million and expanded access across the board.

Pandemic Waivers Transformed Food Distribution

Before the pandemic, organizations participating in the USDA’s *Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) faced numerous restrictions. Meals had to be served on-site in group settings, requiring extensive staffing and daily operations. During the pandemic, however, government waivers temporarily lifted these rules. Instead of requiring daily meal service in specific locations, organizations could distribute multiple days’ worth of meals at once, allowing families to pick up a week’s worth of food in a single trip.

This shift proved to be a game-changer. By moving to a bulk distribution model, the organization reduced the logistical burden of daily operations. Instead of running kitchens and managing distribution daily, they consolidated labor and packing efforts, packing seven days’ worth of food in a day or two.

"Distributing meals weekly rather than daily made a huge difference," said one of the program managers. "We could drastically cut down on transportation, labor, and operational costs while still reaching the same number of kids."

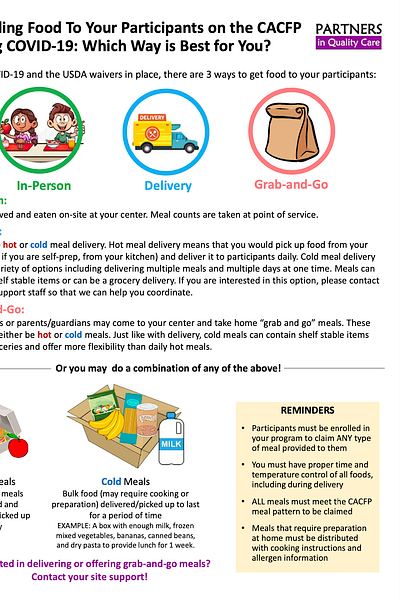

Sponsors promoted new types of food service that are accessible to more organizations.

This flyer (download below) from Partners in Nutrition (PIN) introduces the concept of a cold meal composed of items that may require cooking or preparation. The flyer states, “Cold meal delivery allows a variety of options, including delivering multiple meals and multiple days at one time. Meals can contain shelf-stable items or can be a grocery delivery.”

This change allowed many new ‘vendors’ to enter the business of providing food. You no longer needed hundreds of thousands of dollars of capital to lease a building, purchase kitchen equipment, etc to get into the food service business.

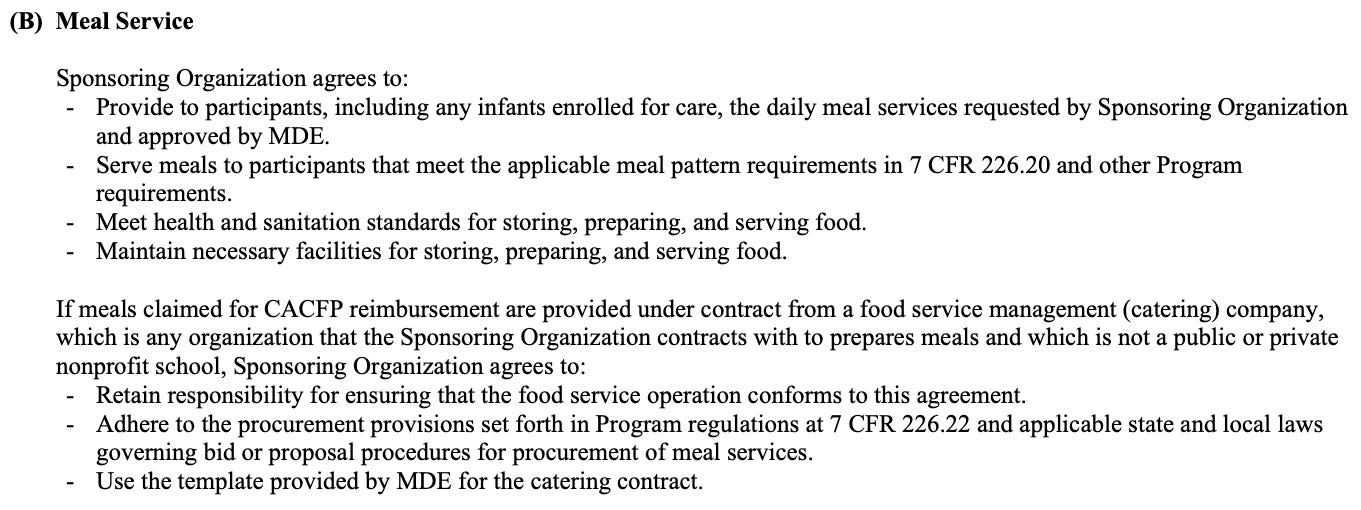

There are strict procurement rules within CACFP and SFSP, but it doesn’t appear these sponsors were following them. In the agreement, every sponsor must sign with the Minnesota Department of Education; it is clear that sponsors must retain responsibility over the catering companies. Below is the excerpted clause from the permanent agreement:

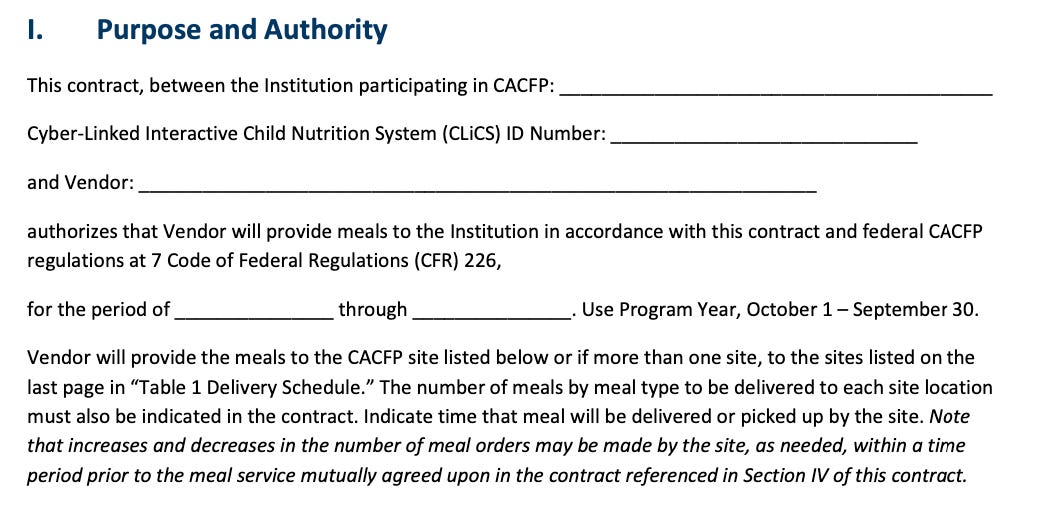

This is mirrored in the standard contract template MDE provides. The first screenshot is at the top of the contract and requires a CLiCS ID, which is only offered once the organization has a signed agreement with MDE to participate in CACFP as a multi-site or single-site sponsor.

This is further reinforced in the contract in this clause, which clearly refers to the agreement with MDE. Once again, only sponsors (multi-site or single-site) enter into such agreements.

But at trial and in other filings, it is clear these sponsors intentionally or unintentionally wanted to shift as much responsibility from themselves onto sites while retaining their administrative fees. Partners in Nutrition was especially egregious in this regard, and I’ll dive deeply into their activities in future posts.

In summary,

Sponsors own the relationships with vendors

Sponsors are responsible for following procurement rules

Sponsors are responsible for ensuring the vendors meet regulations, meal patterns, and other aspects of the food service

Sponsors promoted to these communities new types of meal service, which allowed new ‘vendors’ into the program

This happened while the Minnesota Department of Education was asleep at the wheel. Email correspondence shared with me indicated that MDE didn’t even review vendor contracts submitted by sponsors as part of the site applications. MDE didn’t question whether procurement rules were being followed, and it didn’t conduct any oversight of vendors as required by federal regulations.

Nonetheless, with these waiver rules and new types of food service promoted by sponsors, profit was not only possible, but it was also high.

I’ve crunched the numbers for 3,500 kids for one week. Before we dive into the details, it is worth reminding everyone that kids did not have to attend during the pandemic. Adults were picking up the food. If we assumed each family had five kids, you’d expect about 700 families. I called Dar Al Farooq and discovered that their religious studies program has over 1200 kids enrolled, representing hundreds of families. I couldn’t contact representatives from other youth programs at the center.

For our case study, we will assume a supper and snack are being served. These are being served in bulk with enough food for seven days worth of meals. For the supper and snack meals, the organization planned a simple, bulk-friendly menu:

Supper: Eggs, tortillas, milk, carrots, oranges.

Snack: Cereal boxes and apples.

This menu would require feeding seven suppers and seven snacks to all 3,500 children each week, the following amounts of food per CACFP guidelines:

2,041 dozen eggs

24,500 cereal boxes

43 cases of tortillas

27 bags of carrots

13 bags of oranges

5 bags of apples

382 cases of milk (4 gallons each)

Wholesale food pricing is highly variable, but based on numbers I found from 2021 from Sysco, Upper Lakes, United Foods, Costco, etc., I estimate the total monthly cost of this amount of food would be between $15,000 and $19,000 per week.

What would it take to pack this amount of food?

Packing 24,500 meals per week is labor-intensive but manageable. If each worker packs one meal every 5 minutes into bags or boxes, the vendor must hire 13 people. These 13 people would need to work 8 hours daily for three days to pack all the meals. If they were paid at $20 per hour, the total labor cost for the month would be $23,333.33.

To manage the packing staff and oversee operations, I estimate the vendor would need three managers, each making $5,000 per month. This would bring monthly management costs to $15,000.

What about transportation and storage?

The vendor would need, at a minimum, one reefer box truck, which costs about $2,000 a week to rent, and another $500 per week in diesel fuel. The total monthly transportation costs would be $10,000. Warehouse rent would be approximately $5,000 monthly with $1,500 in utilities.

What about miscellaneous expenses such as bags and other supplies?

Bags and other packing supplies would cost about $1,000 per week, and other miscellaneous supplies would cost an estimated $500. The total for the month would be $6,000.

The Reimbursement Model: No Pandemic Bump, But Profitable Nonetheless

Unlike some might assume, the USDA didn’t significantly increase reimbursement rates due to the pandemic. Instead, these rates are periodically adjusted to reflect the economy and inflation. For CACFP supper and snack, the reimbursement rate was $4.05 combined after sponsor administrative fees were deducted.

With 24,500 meals served per week and $4.05 earned per meal, the vendor generated a total monthly revenue of $396,000.

Calculating the Bottom Line: Turning a Profit

After accounting for food, labor, transportation, facilities, and other operational costs, the total monthly expenses amounted to approximately $140,833. I’ll increase this by 20% to account for undercounting, for a total monthly expense of $168,999.60. With a monthly revenue of $396,000, the organization achieved a monthly profit of $227,000. This is a profit margin of 57.32%

This is also a high watermark and not the likely amount of food needed due to rules around food waste.

Offer vs. Serve (OVS) in the CACFP At-Risk Afterschool program allows children to decline specific food components to reduce waste while still receiving a reimbursable meal. In OVS, all required meal components must be offered, but participants must only take a minimum number of items (4 components). For example, if milk is one of the five components offered at supper, a child can decline the milk and still have the meal reimbursed if they select at least four of the five components, one of which must be a fruit or vegetable. This flexibility helps ensure children can choose the foods they will eat without impacting the meal’s reimbursement. During the pandemic, this meant milk was often declined by families who didn’t have the fridge capacity to store many gallons of milk. This would mean milk numbers might be lower than anticipated without impacting the reimbursable meal.

Why Profit Was Possible: The Key Factors

The ability to turn a profit in a program designed to serve children was due to a combination of factors:

1. Bulk Purchasing and Menu Simplification: Easy-to-source and storefoods and buying in large quantities kept food costs low.

2. Efficient Labor: Packing meals in bulk and distributing them weekly rather than daily allowed the organization to reduce labor hours and transportation costs significantly.

3. Flexible Distribution: The pandemic waivers enabled the organization to simplify logistics by allowing them to distribute meals simultaneously rather than requiring daily meal service.

None of this is to say that the Government isn’t right and the indicted vendors didn’t inflate their numbers, but it is essential to have the proper perspective. It was possible and probable to make a profit in SFSP and CACFP. This is true before, during, and after the pandemic. As this case progresses, government investigators must dive deeper into their assumptions about what was possible. This small example shows food is a tiny part of the costs of delivering food services. The pandemic rules drastically reduced the labor and overhead needed to achieve similar results.